INTERVIEW WITH JEAN COSMOS & JEAN-DANIEL VERHAEGHE

What do you think gives LE GRAND MEAULNES such a unique place in French literature?

JEAN COSMOS: It's a novel written by a post-adolescent and I think that's its key virtue. In my mind, Alain-Fournier wrote it for himself, with a great deal of ingenuousness. He was still fairly young. The novel was published in 1913 when he was only 27. For a young man that age, and, what's more, who tried to get into Normal School, it's not arcane, but in fact rather fluid. The novel is fairly autobiographical. The character of Yvonne was inspired by a young woman he met on a Paris boulevard and with whom Alain-Fournier had little contact, simply a passing conversation, but one that would haunt his adolescent years. And that's what the novel is about. It's the story of a rather frustrated young man who glimpses a silhouette, dreams about it and builds his life around that dream.

What is amazing when you begin to read this book with a technical eye, so to speak, is that you don't know where the magnetism resides, but it's everywhere. That's something unique in modern literature. The virtue of LE GRAND MEAULNES is its magnetism, its mystery. And when you undertake to make a movie out of such a hazy novel, by which I mean without precise form, in which fate is not clearly outlined, the hyperrealism of motion pictures becomes treacherous. Yvonne on the screen no longer belongs to you. Nor does Meaulnes. Whereas, when you read it, only your imagination is engaged.

JEAN-DANIEL VERHAEGHE: Nor should we forget that the book is a narrative told in the third person. Which reflects the fascination Meaulnes already exerts over the narrator. He's someone who bursts into his life and changes both him and the way he looks at things. To a certain extent, I tend to see Meaulnes as Pasolinian. By which I mean someone who arrives, passes through and changes the persons around him.

JC: Which is exactly how the novel opens: "Someone came and changed my life."

J-DV: "An angel passes." It's also one of the problems inherent in the movie because he's absent for a long while in the story. Without providing any explanation. Ultimately, you wonder if he isn't an objectionable character. He abandons his fiancée, his wife, and is only heard from again two years later.

Is the book inspired by Romanticism?

JC: Yes. And at the same time, the book is bathed in pseudo-naturalism because the best-written sections — and easiest for us to render — are what Alain-Fournier knew well: the life of a schoolteacher. The school, the small town world, his unexceptional life. He came from this world, he was trained at the Normal School and his aim was to become a teacher. I'm very sensitive to this realistic element, which we find in his description of the Sologne region. You feel that the scene in which the children go swimming comes from a real experience. Those scenes are well suggested. In fact, I think that LE GRAND MEAULNES is more a work of suggestion than of description. We only know Meaulnes by a series of little touches. The same goes for Yvonne. It's almost more impressionistic than romantic. Alain-Fournier wasn't a follower of any particular school and that's what makes him strange. He's hard to pigeonhole. In his work, you find various influences going from the Symbolists to Claudel, not to mention Gide, who left a deep impression on him. He doesn't really know where he's going. Finally, he follows a route that only he can follow.

Can we call it a novel of initiation?

JC: I think that in an initiation narrative, the one who is initiated has a certain desire to pass something on, to make things move.

J-DV: My impression is that in the initiation novel there is the idea of a secret, which doesn't exist here.

JC: Life doesn't seem to have much of a hold on Meaulnes. His complicated loves don't lead him to a perception, a passing on of any precise romantic sentiment. I think what we have here is more of a sketch, an evocation and in no way an affirmation. So we're rather far from the idea of initiation.

J-DV: For me its both a regionalist, realistic novel, because it takes place in a very specific setting, and at the same time, it's a love story, lighting striking Meaulnes and this young girl, Yvonne, whom he glimpses at the chateau. So we have here the entire framework of a romantic tale, but at the same time it's also a story of a transmission of love. What's also very interesting in this novel is how the narrator in turn falls in love with Yvonne, how he takes over his friend's romance. LE GRAND MEAULNES is the story of this passage from childhood to adolescence, the story of François who awakens to love, which is a feeling he dares not acknowledge and which Meaulnes passes on to him. It's both love as a personal experience and love transferred. There is a fantastical, dreamlike episode in the book that is rather surprising because it removes it from this naturalist dimension you talk about.

J-DV: The fete itself is fairly realistic. If the novel speaks of a "strange" fete, it's because Meaulnes comes across it when he gets lost. He doesn't know where he is. And then there's the appearance of Monsieur de Galais who is like a character out of Alice in Wonderland. What's more, he owns a watch that will be important later since it enables the watchmaker to be located. And then there is that suspended, timeless moment, which is the meeting with Yvonne. And, finally, the strangeness, or in any case, the unexpected, comes with Franz's entrance, in that carriage that arrives without the bride and the guests who gather up their gifts and leave.

The forest Meaulnes crosses to reach the chateau echoes fairy tales and tales of chivalry where it usually symbolizes a passageway to something else.

JC: The "something else" in LE GRAND MEAULNES is the reality it reflects. From this perspective, the fete is a kind of imaginary island. Will he ever find it again?

The process will take time and a good part of the action. True, there is something chivalrous in the characters’ behavior. It echoes a time when romantic love was dominant. You promise to love, you give your word. It's extraordinary. Meaulnes gives up all that is dearest to him to fulfill a pledge he gave one night to a young man. That's also very chivalrous.

J-DV: This idea of the pledge is very important. The concept is hard to accept in our day and age, but it is still the stuff of dreams. I insisted on the idea of the handshake in the attic between Franz and Meaulnes, when Meaulnes swears he will help his friend find his beloved. For which he will go so far as to leave Yvonne.

JC: It's also very juvenile. And it probably echoes the vows Alain-Fournier made to Rivière, his classmate at Lakanal and Normal School. They are young men who make lifelong promises to each other. So it's very similar to the author's behavior and he passes it on to his characters.

How do you explain the book's continuing fascination and appeal for new generations?

JC: It mostly has to do with the novel's charm and its first section. Anyone who has read LE GRAND MEAULNES can easily describe what happens right up to the strange fete. But then, with the story of the bohemians for example, things become less clear. From that point on we're in another story. And Jean-Daniel quickly rallied to the belief that we would have problems with contemporary audiences more responsive to a certain Cartesian logic from which the novel takes it distance in this second part. What we thought we needed — if even it's just barely outlined in the book — was to take things in the direction of Valentine, whom Meaulnes tracks down. She then becomes the new Yvonne, but much more plebian.

J-DV: François is the one who reminds Meaulnes of his promise and brings him back to Yvonne, because he's appropriated his love story. He's made a pledge, too. Each honors his commitment.

JC: I think it's these values, far removed from our own time, which continue to explain why new generations respond to the novel. Love in LE GRAND MEAULNES is a kind of ideal. The love for a distant Princess. Teenagers — now that they're used to living out their desires, which doesn't put them in a position to make their way toward real life in any concrete manner — have great uncertainty as regards romantic feeling. They don't commit. The idea of fidelity, when it comes up, scares them. But fidelity is one of the mainsprings of the novel. You're faithful to a promise made, to the image glimpsed. There's only one woman in your life.

J-DV: It's love born of a gaze. It's also, for Yvonne – we've only dealt with Meaulnes' point of view until now — an absolute love. If she lets him go, it's because she knows this is the life of the one she loves. There's a magnificent line in the novel where she says that he mustn't be unhappy because his life is also her life. She understands him. She leaves him his liberty. She accepts the fact that he's gone off to honor his word. She's never angry with him.

It's also a magnificent story of friendship. Is that something that still speaks to young people today, a century later?

Of course. And Alain-Fournier's heroes aren't people who talk in onomatopoeia inside balloons. When they speak, they say something. For a young man or woman, encountering people of this quality is fascinating. They identify with them. They become their Yvonne de Galais or their Meaulnes. There's something timeless in the charm, something that can dazzle, or in any case, fill you with desires. I think they still long for that.

J-DV: In the book, the idea of Meaulnes's first entrance is magnificent. He doesn't speak to François. He just says, "Coming?" because he's found something in the attic and that's that. They look at one another, exchange a smile. No explanations. It's obvious. He shows him around a place François knows by heart and yet he rediscovers it. And Meaulnes does the same with his friend's feelings.

JC: The interrupted fete contains it all in a nutshell. Meaulnes forces events. He asserts himself. He has spirit. He walks in, people look at him. He appears and he's seen. There's something animalistic in him, totally natural, without any twisted psychological background.

J-DV: Moreover, he inspires both immediate friendship and spontaneous enmity when he appears in class. He leaves no one indifferent. The "something else" in LE GRAND MEAULNES is the reality he reflects back to us.

A word about Alain-Fournier's style?

JC: It's unique. Especially in the way he always suggests things, without defining them. Except when it's something that won’t affect the ambiance of the book. For instance, he can evoke the classroom with precision — the smell of chalk and ink — because it's a personal experience. But on the other hand, in the dream part, there is a great sense of freedom. His style is very fluid, very pure, very smooth. It's a novel you read with wonderful rapidity. But that doesn't mean it's superficial.

How do you adapt a novel like that?

JC: The ground rule, with a book like this, is fidelity or transgression. I never take the second option. I see it as some kind of a swindle. You take a title, a book's reputation and you turn it into something else entirely different. Sure, with a book as widely read as LE GRAND MEAULNES, you're obviously forced to betray it a little, but it's never an objective at the start. It remains a necessity, an obligation. I'm all for fidelity and so is Jean-Daniel.

J-DV: What we deliberately changed was the ending. In the book, Meaulnes goes off with his child. And in our script, we tied it to Alain-Fournier's life. To a certain extent, the hero becomes one with his author.

JC: Right from the start, we wanted to link the writer's tragic end with his novel, so that audiences would understand that it's the book of a very young man who won't live long. It's a legacy, but not intended as one. The book came out 18 months before the author died in the war. We couldn't ignore that. Which gives us a different ending that I don't find more pessimistic, because there's a transfer of paternity to François. François will survive since he is the narrator and the little girl represents the future.

How did you approach the shooting? What were your requirements, what were your ambitions?

J-DV: Images come when they're in the screenplay. It has to be obvious. You have to be totally wrapped up in it. If you are, you know how to film it. And I've always been respectful of books and scripts because I've virtually done nothing but adaptations. I'm like a go-between, in the service of a work. And at the same time, I've always considered that turning a book into a movie was tantamount to doing a good textual analysis. In other words, making audiences understand — and this via the script first of all — the themes and things we sought to bring out. In this case, the themes are love, the first glance, the promise made. Then, we have to render the ambiance, find the music. There are scenes that we gauge as being more rapid, with camera movements… The shooting script always depends on the musicality of a scene, the way it's going to be shot. The hardest scene to film was probably that of the encounter around the piano. Everyone knows it, everyone is waiting for it. We're obliged to impose our view. For me the rule is never to add poetry when it's already there. It has to come on its own, and that's probably what Jean means by the magnetism. Don't overdo it, don't underline anything with slow motion or whatever since it's already there. You have to do things with simplicity.

Another hurdle: the casting. You have to embody mythical heroes. Figures that no two readers identify with in the same way. How did you go about finding the actors?

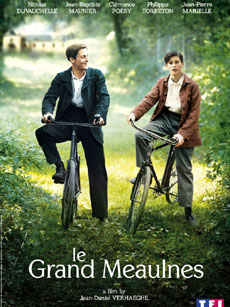

J-DV: First of all, we spent a long time looking for our Meaulnes. What I appreciate most about Nicolas Duvauchelle is that contemporary side he has. He has integrity, he is natural, a side of his personality that, to me, spontaneously brings him closer to Meaulnes. As for the role of François, Jean-Baptiste Maunier was a perfect match. In the book, he's the narrator, a voice-over — which is not easy to make work in a movie — but he's also the one who's going to look for Meaulnes. He's the main thread. He remains. Unlike Meaulnes, who passes. And Jean-Baptiste Maunier, who was only 15 at the time of shooting, amazed us with his skill and maturity. Yvonne was harder to cast. What I love about Clemence was her "incarnation of an ideal woman" side, the kind whom we fall in love with at first glance. She's the kind of woman who tends to be confined, in people's minds, to being an abstraction, as Jean says. But she truly lives and loves. On the other hand, Valentine embodies the world of joy, work and popular dance halls… Emilie impressed us as being the obvious choice. I didn't know her, but she struck me as being exactly like her role: part of life.

INTERVIEW WITH

JEAN COSMOS & JEAN-DANIEL VERHAEGHE

What do you think gives LE GRAND MEAULNES such a unique place in French literature?

JEAN COSMOS: It's a novel written by a post-adolescent and I think that's its key virtue. In my mind, Alain-Fournier wrote it for himself, with a great deal of ingenuousness. He was still fairly young. The novel was published in 1913 when he was only 27. For a young man that age, and, what's more, who tried to get into Normal School, it's not arcane, but in fact rather fluid. The novel is fairly autobiographical. The character of Yvonne was inspired by a young woman he met on a Paris boulevard and with whom Alain-Fournier had little contact, simply a passing conversation, but one that would haunt his adolescent years. And that's what the novel is about. It's the story of a rather frustrated young man who glimpses a silhouette, dreams about it and builds his life around that dream.

What is amazing when you begin to read this book with a technical eye, so to speak, is that you don't know where the magnetism resides, but it's everywhere. That's something unique in modern literature. The virtue of LE GRAND MEAULNES is its magnetism, its mystery. And when you undertake to make a movie out of such a hazy novel, by which I mean without precise form, in which fate is not clearly outlined, the hyperrealism of motion pictures becomes treacherous. Yvonne on the screen no longer belongs to you. Nor does Meaulnes. Whereas, when you read it, only your imagination is engaged.

JEAN-DANIEL VERHAEGHE: Nor should we forget that the book is a narrative told in the third person. Which reflects the fascination Meaulnes already exerts over the narrator. He's someone who bursts into his life and changes both him and the way he looks at things. To a certain extent, I tend to see Meaulnes as Pasolinian. By which I mean someone who arrives, passes through and changes the persons around him.

JC: Which is exactly how the novel opens: "Someone came and changed my life."

J-DV: "An angel passes." It's also one of the problems inherent in the movie because he's absent for a long while in the story. Without providing any explanation. Ultimately, you wonder if he isn't an objectionable character. He abandons his fiancée, his wife, and is only heard from again two years later.

Is the book inspired by Romanticism?

JC: Yes. And at the same time, the book is bathed in pseudo-naturalism because the best-written sections — and easiest for us to render — are what Alain-Fournier knew well: the life of a schoolteacher. The school, the small town world, his unexceptional life. He came from this world, he was trained at the Normal School and his aim was to become a teacher. I'm very sensitive to this realistic element, which we find in his description of the Sologne region. You feel that the scene in which the children go swimming comes from a real experience. Those scenes are well suggested. In fact, I think that LE GRAND MEAULNES is more a work of suggestion than of description. We only know Meaulnes by a series of little touches. The same goes for Yvonne. It's almost more impressionistic than romantic. Alain-Fournier wasn't a follower of any particular school and that's what makes him strange. He's hard to pigeonhole. In his work, you find various influences going from the Symbolists to Claudel, not to mention Gide, who left a deep impression on him. He doesn't really know where he's going. Finally, he follows a route that only he can follow.

Can we call it a novel of initiation?

JC: I think that in an initiation narrative, the one who is initiated has a certain desire to pass something on, to make things move.

J-DV: My impression is that in the initiation novel there is the idea of a secret, which doesn't exist here.

JC: Life doesn't seem to have much of a hold on Meaulnes. His complicated loves don't lead him to a perception, a passing on of any precise romantic sentiment. I think what we have here is more of a sketch, an evocation and in no way an affirmation. So we're rather far from the idea of initiation.

J-DV: For me its both a regionalist, realistic novel, because it takes place in a very specific setting, and at the same time, it's a love story, lighting striking Meaulnes and this young girl, Yvonne, whom he glimpses at the chateau. So we have here the entire framework of a romantic tale, but at the same time it's also a story of a transmission of love. What's also very interesting in this novel is how the narrator in turn falls in love with Yvonne, how he takes over his friend's romance. LE GRAND MEAULNES is the story of this passage from childhood to adolescence, the story of François who awakens to love, which is a feeling he dares not acknowledge and which Meaulnes passes on to him. It's both love as a personal experience and love transferred. There is a fantastical, dreamlike episode in the book that is rather surprising because it removes it from this naturalist dimension you talk about.

J-DV: The fete itself is fairly realistic. If the novel speaks of a "strange" fete, it's because Meaulnes comes across it when he gets lost. He doesn't know where he is. And then there's the appearance of Monsieur de Galais who is like a character out of Alice in Wonderland. What's more, he owns a watch that will be important later since it enables the watchmaker to be located. And then there is that suspended, timeless moment, which is the meeting with Yvonne. And, finally, the strangeness, or in any case, the unexpected, comes with Franz's entrance, in that carriage that arrives without the bride and the guests who gather up their gifts and leave.

The forest Meaulnes crosses to reach the chateau echoes fairy tales and tales of chivalry where it usually symbolizes a passageway to something else.

JC: The "something else" in LE GRAND MEAULNES is the reality it reflects. From this perspective, the fete is a kind of imaginary island. Will he ever find it again?

The process will take time and a good part of the action. True, there is something chivalrous in the characters’ behavior. It echoes a time when romantic love was dominant. You promise to love, you give your word. It's extraordinary. Meaulnes gives up all that is dearest to him to fulfill a pledge he gave one night to a young man. That's also very chivalrous.

J-DV: This idea of the pledge is very important. The concept is hard to accept in our day and age, but it is still the stuff of dreams. I insisted on the idea of the handshake in the attic between Franz and Meaulnes, when Meaulnes swears he will help his friend find his beloved. For which he will go so far as to leave Yvonne.

JC: It's also very juvenile. And it probably echoes the vows Alain-Fournier made to Rivière, his classmate at Lakanal and Normal School. They are young men who make lifelong promises to each other. So it's very similar to the author's behavior and he passes it on to his characters.

How do you explain the book's continuing fascination and appeal for new generations?

JC: It mostly has to do with the novel's charm and its first section. Anyone who has read LE GRAND MEAULNES can easily describe what happens right up to the strange fete. But then, with the story of the bohemians for example, things become less clear. From that point on we're in another story. And Jean-Daniel quickly rallied to the belief that we would have problems with contemporary audiences more responsive to a certain Cartesian logic from which the novel takes it distance in this second part. What we thought we needed — if even it's just barely outlined in the book — was to take things in the direction of Valentine, whom Meaulnes tracks down. She then becomes the new Yvonne, but much more plebian.

J-DV: François is the one who reminds Meaulnes of his promise and brings him back to Yvonne, because he's appropriated his love story. He's made a pledge, too. Each honors his commitment.

JC: I think it's these values, far removed from our own time, which continue to explain why new generations respond to the novel. Love in LE GRAND MEAULNES is a kind of ideal. The love for a distant Princess. Teenagers — now that they're used to living out their desires, which doesn't put them in a position to make their way toward real life in any concrete manner — have great uncertainty as regards romantic feeling. They don't commit. The idea of fidelity, when it comes up, scares them. But fidelity is one of the mainsprings of the novel. You're faithful to a promise made, to the image glimpsed. There's only one woman in your life.

J-DV: It's love born of a gaze. It's also, for Yvonne – we've only dealt with Meaulnes' point of view until now — an absolute love. If she lets him go, it's because she knows this is the life of the one she loves. There's a magnificent line in the novel where she says that he mustn't be unhappy because his life is also her life. She understands him. She leaves him his liberty. She accepts the fact that he's gone off to honor his word. She's never angry with him.

It's also a magnificent story of friendship. Is that something that still speaks to young people today, a century later?

Of course. And Alain-Fournier's heroes aren't people who talk in onomatopoeia inside balloons. When they speak, they say something. For a young man or woman, encountering people of this quality is fascinating. They identify with them. They become their Yvonne de Galais or their Meaulnes. There's something timeless in the charm, something that can dazzle, or in any case, fill you with desires. I think they still long for that.

J-DV: In the book, the idea of Meaulnes's first entrance is magnificent. He doesn't speak to François. He just says, "Coming?" because he's found something in the attic and that's that. They look at one another, exchange a smile. No explanations. It's obvious. He shows him around a place François knows by heart and yet he rediscovers it. And Meaulnes does the same with his friend's feelings.

JC: The interrupted fete contains it all in a nutshell. Meaulnes forces events. He asserts himself. He has spirit. He walks in, people look at him. He appears and he's seen. There's something animalistic in him, totally natural, without any twisted psychological background.

J-DV: Moreover, he inspires both immediate friendship and spontaneous enmity when he appears in class. He leaves no one indifferent. The "something else" in LE GRAND MEAULNES is the reality he reflects back to us.

A word about Alain-Fournier's style?

JC: It's unique. Especially in the way he always suggests things, without defining them. Except when it's something that won’t affect the ambiance of the book. For instance, he can evoke the classroom with precision — the smell of chalk and ink — because it's a personal experience. But on the other hand, in the dream part, there is a great sense of freedom. His style is very fluid, very pure, very smooth. It's a novel you read with wonderful rapidity. But that doesn't mean it's superficial.

How do you adapt a novel like that?

JC: The ground rule, with a book like this, is fidelity or transgression. I never take the second option. I see it as some kind of a swindle. You take a title, a book's reputation and you turn it into something else entirely different. Sure, with a book as widely read as LE GRAND MEAULNES, you're obviously forced to betray it a little, but it's never an objective at the start. It remains a necessity, an obligation. I'm all for fidelity and so is Jean-Daniel.

J-DV: What we deliberately changed was the ending. In the book, Meaulnes goes off with his child. And in our script, we tied it to Alain-Fournier's life. To a certain extent, the hero becomes one with his author.

JC: Right from the start, we wanted to link the writer's tragic end with his novel, so that audiences would understand that it's the book of a very young man who won't live long. It's a legacy, but not intended as one. The book came out 18 months before the author died in the war. We couldn't ignore that. Which gives us a different ending that I don't find more pessimistic, because there's a transfer of paternity to François. François will survive since he is the narrator and the little girl represents the future.

How did you approach the shooting? What were your requirements, what were your ambitions?

J-DV: Images come when they're in the screenplay. It has to be obvious. You have to be totally wrapped up in it. If you are, you know how to film it. And I've always been respectful of books and scripts because I've virtually done nothing but adaptations. I'm like a go-between, in the service of a work. And at the same time, I've always considered that turning a book into a movie was tantamount to doing a good textual analysis. In other words, making audiences understand — and this via the script first of all — the themes and things we sought to bring out. In this case, the themes are love, the first glance, the promise made. Then, we have to render the ambiance, find the music. There are scenes that we gauge as being more rapid, with camera movements… The shooting script always depends on the musicality of a scene, the way it's going to be shot. The hardest scene to film was probably that of the encounter around the piano. Everyone knows it, everyone is waiting for it. We're obliged to impose our view. For me the rule is never to add poetry when it's already there. It has to come on its own, and that's probably what Jean means by the magnetism. Don't overdo it, don't underline anything with slow motion or whatever since it's already there. You have to do things with simplicity.

Another hurdle: the casting. You have to embody mythical heroes. Figures that no two readers identify with in the same way. How did you go about finding the actors?

J-DV: First of all, we spent a long time looking for our Meaulnes. What I appreciate most about Nicolas Duvauchelle is that contemporary side he has. He has integrity, he is natural, a side of his personality that, to me, spontaneously brings him closer to Meaulnes. As for the role of François, Jean-Baptiste Maunier was a perfect match. In the book, he's the narrator, a voice-over — which is not easy to make work in a movie — but he's also the one who's going to look for Meaulnes. He's the main thread. He remains. Unlike Meaulnes, who passes. And Jean-Baptiste Maunier, who was only 15 at the time of shooting, amazed us with his skill and maturity. Yvonne was harder to cast. What I love about Clemence was her "incarnation of an ideal woman" side, the kind whom we fall in love with at first glance. She's the kind of woman who tends to be confined, in people's minds, to being an abstraction, as Jean says. But she truly lives and loves. On the other hand, Valentine embodies the world of joy, work and popular dance halls… Emilie impressed us as being the obvious choice. I didn't know her, but she struck me as being exactly like her role: part of life.

Print

Print