How was this project born?

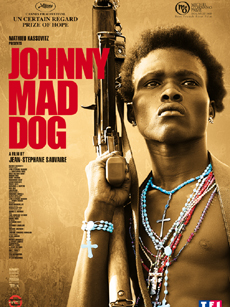

CARLITOS MEDELLIN, which I filmed in Columbia, was originally meant to be a fiction of Medellinâs boys fighting against the FARC. This proved difficult and the project became a documentary on the spot. After this experience I discovered Emmanuel Dongalaâs book «Johnny Chien Mechant», which deeply moved me. I saw in it the possibility of pursuing the project, to move towards fiction based on a similar subject: that of children plunged into the violence of armed conflicts. This was in 2003, and rather than focus on writing an original script, I wanted to start with a classic narrative structure taken from a book and confront it to the reality of the terrain. To blend a literary work with something more documentary and realistic.

Why choose to film in Liberia?

It was primordial for me to work with ex-children soldiers, who seemed to be the only ones capable of giving a sincere testimony of this horror. Liberia was not an easy choice at this time; the war had ended in August 2003 and a transitional government had been set up. Ellen Johnson Sirleafâs election in January 2006 made filming in Liberia possible. We really sensed the governmentâs support, its desire to welcome us, its need to give testimony.

What was important was to say that we would speak of children soldiers, a subject which has touched Liberia; but it is also a way to show that today the country is stable enough for us to shoot a movie in it.

For Liberians, it was a way to assess before the international community that they had moved on, that they had turned the page after 15 years of war.

Was security a determining factor?

We had to be able to film in peace, not in between three gunshots like in Medellin. Filming fiction in a place where there is shooting everywhere can be at once out of place and complicated. We needed stability. At the same time, Liberia still wore all the stigmata of war and the people wanted to speak, to testify of it: that was the most important. To be alone facing only yourself while working on a film like this one was out of the question: I felt all this strength, this energy, all this desire behind me.

Were you able to avoid a too âofficialâ recuperation of the film?

No one tried to influence the project. The Liberian presidentâs support -Ellen Johnson-Sirleafâs- has avoided us pressures and resistances. When I began casting and I entered the heart of the matter, I spent nearly a year going to see Charles Taylorâs or Lurdâs ex-generals with whom I made ties and explained our project. But I was never reproached anything; on the contrary everyone entered the adventure pretty naturally.

How did you find the ex-children soldiers who play in your movie?

I first turned to the NGO on the spot before realizing that they kept to very specific networks. I then felt the need to go on the field. I focused on Monrovia and the ghetto zones surrounding the city. The ex-generals pointed out war leaders who were in charge of the children at the time. I was organizing castings in the districts with those who had fought. I must have seen 500 or 600 children to choose 15 of them. Amidst these children, I had to find those who stood out from the crowd, who had the personality to act. It was a long-winded though fascinating task, which allowed me to understand a lot of things and to meet the true actors of these conflicts.

And what of the two main characters, Laokole and Johnny?

I found Daisy very late in the process, a month before shooting: we noticed her in the street, she auditioned and we took her. It

was in evidence. Johnny I met in 2005 in the district of New Kru town through the medium of Warboy, alias Young Major in the movie. He had the reputation of having long fought and he was the one to introduce Johnny to me, one of his children soldier friends. Johnny was too young at the time, he was 13 years old and I didnât want a 12-13 year old child caught up in the murderous madness as is No Good Advice in the movie; I wanted rather an adolescent on the brink of slipping, who begins to gain an awareness of death, of his actions etc.

The movie was postponed, and with time Babyboy, alias Johnny turned out to be perfect for the role. He fought towards the end in 2003 for the Lurd (Liberians United for Reconciliation and Democracy).

Was preparation crucial?

We had to find the children, but also gain their trust. A number told us: journalists come, interview us and disappear. I then explained to them that for a film, I would have to leave and return, go back and forth, invest myself for the long run. I finally moved in with them for a year in a house in Monrovia to instill this trust, prepare the project and begin to work together. 15 ex-children soldiers who have no family structure and have never gone to school, who know no liberty but that of the street, are not necessarily ready to enter a system like that of filming, which implies a certain work discipline. Curiously, the fact that they had fought in opposite camps on the other hand was not a problem; for them that was past and they even prided themselves on having fought, whatever the side. This preparation also allowed me to master and to understand English as it is spoken in the districts of Monrovia - a very phonetic English, pretty crude and instinctual. We ended up understanding each other very easily and a long preparation such as that one had been indeed crucial.

How did you initiate the children to actorâs work?

There was the script, but the children couldnât read. At the beginning, I let them improvise on the scenes: I would explain the sequence to them and I would ask them to improvise while I filmed them. It was also a way to familiarize them with the camera and to instill a game system: to have fun with it. They improvised and then saw themselves in the television, understood that they shouldnât look at the camera, talk all at the same time, in short understand how a movie is made. After, there was a large coaching process with Karine Nuris, based on exercises - a way of saying «Ok, you have your experience, but now you have to enter a discipline, you are actors and you must work, that is to say know how to bring out an emotion, control it, cry, laugh, be angry etc.» By mixing up both, the children very quickly understood the notion of game and of character.

How do you manage the fact that the children has experienced the reality of most of the scenes?

It was approached as a therapy: not like something traumatizing, but like a game. Indeed, these were situations they had experienced but the theater can be therapeutic - it was furthermore used by the NGo during reinsertion - and what was at stake in the film was to rebuild their trust, to evacuate those traumas, to speak of it together, to share. If I had sensed the slightest trauma at re-enacting certain scenes, I would have never continued.

How did you find a balance between this «reality» and the interpretative work in its literal sense?

I re-wrote the film a lot according to their improv and to what they were suggesting. What was most complicated was that the children were not really aware of the scenario: every day on set, I asked myself if they were going to bring out what they had amassed during the preparation process. But we had rehearsed so much that at the end of a year it had become natural. They were immediately in character. The children did not see the scenario as a whole but were aware of the scenes in themselves, of a sort of journey to realize -to fight the ethnicity in power, to cross the bridge, to set fire to the city and overthrow the president, by in large the scheme as it occurred during the war and that they knew perfectly well. There wasnât really any reconstruction of the puzzle, from beginning to end, but a logical movement which imposed itself. Johnny is the only one to remove himself from this dynamic: he becomes aware little by little of the absurdity of the situation and of the reality of death.

A way to remain concrete?

We can only be concrete. one day, Warboy told us of an episode he had experienced: a woman wanted to cross the frontlines, she attempted to discuss the matter and they disemboweled her. They found a baby in her abdomen and partied all night: it is in this state of madness without limit that war puts one. I am shocked by the journalists who arrive and ask the children how many people theyâve killed. We would never ask a Second World War veteran how many people heâs killed, itâs an aberration. We are not faced with serial killers, but with soldiers put in a particular state. They kill so as to not get killed, manipulated by their superiors and caught up in this conditioned madness by very precise rituals: costumes, nicknames, the group, drugs -everything contributes to never being yourself, only a killing machine.

What were your objectives for the filming?

The basis for me is to film people I love and to believe in the

veracity of the situation I have to stage. I donât have the ability to recreate everything, I need the story to be there and

to become obvious to film. Hence the importance of shooting in a country like Liberia, with people who bring in their own experience. I sought to never cheat or negotiate the childrenâs vision, I wanted only to get closer to the truth. What was important was not to lecture but to content ourselves with retranscribing reality as it offers itself to us. And at the same time, itâs about inscribing it in fiction because itâs cinema and not a documentary, with a story which takes shape.

What was at stake was to find this balance between documentary energy and this story which was building itself. Hence also the use of the scope format, which is a more fiction-oriented format. Iâve always had difficulty entering the debate on the aesthetics of horror. Be it in a shoulder-DV realism or in a more cinematic format, the question is the same: how can we and must we show reality in a neutral light? From the moment there is a camera, there is a point of view and a way of narrating which imposes itself.

The filmâs movement is very direct, were you aiming at stripping it of unnecessary stylistic devices?

Everything is determined by this immediacy, this importance of the present moment, this spiral in which the children are propelled. During the war, distancing themselves and reflecting is not possible for them. The system of indoctrination with the use of drugs, songs, rituals or the mechanics of a group force us to move forward all the time. It becomes impossible to recede, as we were explaining to one of the children during his casting -if you withdraw, you get shot, so you donât have any choice but to keep moving forward. But I didnât want to consider them strictly as innocent children entering combat against their will; they take to this game of war, regret can only come after the fact.

Like?

He invested himself in the beginning, in script-writing and in the editing process. It was interesting because heâs not only a producer, but also a director and heâs a instinctive and talented person. He is able to put his finger on specific things,

and pushed me to radicalize the film, to recenter it on the story where I would have wished to pull it towards something more sensory and formal. Heâs an respectful person, who understands perfectly the doubts and difficulties you can have as a director. He and Benoit Jaubert stuck by me to the end, which was not always easy and was brave on their part.

Now that filming has ended, do you remain in touch with the children?

It was unimaginable for me to reproduce the scheme the children had known during the war: the general comes, takes the children and abandons them as soon as itâs over. The year of preparation and the filming created very strong ties, a very cohesive group sentiment. I wanted to continue following the childrenâs progress, trying to help them in their reinsertion. During the preparation, classes were held every morning. We have kept the educator since, a house and created the foundation âJohnny Mad Dogâ where they know they can turn to to eat, attends courses, sleep, be listened to etc.

These children still live day-to-day, hour after hour, with a logic of survival which is hard to conciliate with a long-term project. Thatâs what must be addressed. But itâs also from this immediacy that they have derived their strength during filming: they experienced everything in the present moment, they gave an enormous amount of themselves. I think itâs strongly present in the film and for that I thank them.

I hope this film will be an opportunity to address the problem of child soldiers in the world which unfortunately, is still a topical issue and remains nonetheless unacceptable and intolerable.

EXTRACTS FROM THE INTERVIEW BY VINCENT MALAUSA

How did you meet Jean-Stéphane Sauvaire, the director?

Benoit Jaubert: I have produced a short movie that he had directed in 1991. It was the time of SAVAGE NIGHTS (a film by Cyril Collard) where Jean-Stéphane was an assistant.

Mathieu Kassovitz: Yes, weâve known Jean-StĂ©phane for the past 17 years. I knew him at the time when he was an assistant, like me. We used to meet all the time.

When was the project of Johnny Mad Dog born?

M.K.: Jean-StĂ©phane came to see us in 2004 on his way back from Colombia and he showed us a documentary he had shot there, CARLITOS MEDELLIN. He also told us about Emmanuel Dongolaâs novel âJohnny Mad Dogâ and he told us he wanted to adapt it at any cost.

B.J.: He had already written a first draft of the screenplay, we found it fascinating and decided to join in the project. Mathieu immediately started working on the screenplay with him.

What attracted you in this project?

M.K.: When we watched CARLITOS MEDELLIN, we sensed the eagerness of Jean-StĂ©phane to bring back images from the most unlikely places, but mostly because he had a very good feeling with people, especially children. We said to ourselves: we donât know what would come out of him in a fiction, but if he gets the go-ahead and a solid screenplay, we can let him go for it.

B.J.: We had also seen his short movies, such as THE MULE, and especially small films shot in Mexico with children going wild during pagan feasts and celebrations of the devil amidst bombs and fireworks.

Was the choice of shooting in liberia an option from the onset?

M.K.: At the beginning, I was just back from the shooting of MUNICH and launching BABYLON A.D. We spent a year working on the screenplay, knowing we had little stuff to start with, and having no idea as to where the shooting would take place. The only certainty was that we wanted a country that had gone through a civil war, which was not to the liking of our insurers! At the same time Jean-StĂ©phane wanted to move away from History with a capital H! In the movie, Liberia is never mentioned, itâs a universal story dealing with the reality of any country going through civil war.

B.J.: At first, we were supposed to shoot in a Frenchspeaking African country; then we realized that the issue of children soldiers in western Africa had mainly hit English speaking countries. on his way back from a trip to Sierra Leone and Liberia, Jean-StĂ©phane told us that we absolutely had to shoot in Liberia! We told him: youâre nuts! The fact of breaking away from French-speaking countries posed a few problems in terms of advances on contracts. Moreover the English spoken in Monrovia is rather special: in film financing, language is decisive, so we were already sure we would have sub-titles in all the territories! That wasnât making things easyâŠ

How is it to prepare a shooting in liberia where no movie has ever been shot?

B.J.: We always loved to shoot in unlikely countries, like Vietnam for example, not only to take up challenges, but because the authenticity of a movie is also determined by the location of the shooting. So we consulted the insurances, they followed us on the project, and we realized that conditions were rather favourable: Liberia was entering a period of moratorium and the President Ellen Johnson-Sirlea, who had just been Elected, had undertaken the eradication of corruption and changed things in-depth.

M.K.: We arrived during that reconstruction period: the disarmament, the trial of Charles Taylor, etc. Thatâs without counting the 15000 UN soldiers posted there to guarantee security.

What were the relations with the people there like?

B.J.: We got there with our project not knowing what will come out of it. But we received the authorisations from the Ministry of Culture and Youth, and the president herself gave us her blessing and assigned a maximum of people on the project. Everything was arranged with the local notaries. The Liberian law is a copy of the American one, itâs rather complex, so we had to play it clean: we had tutors all the time, children went to school in the mornings, etc. Everything was official up to fees and bank operations, etc.

M.K.: Seeing the extent to which the whole country was in reconstruction logic, we tried to be as responsive as possible and be up to the task. In a way, the national reconciliation process was a permanent backing to our project.

And from a technical and logistic point of view?

B.J.: From the point of view of infrastructures, there was absolutely nothing; but the main problem came from the total embargo on arms. We contacted the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the United Nations, and the American Secretary of State to lift the embargo for the demilitarised arms but to no avail. Shooting a war movie where there are constant shootings makes it much more complicated obviously! Though the United Nations finally gave us some arms from the stocks they had recuperated there.

M.K.: Weâve mainly used âtoysâ replicas.

How did shooting go with the local population?

B.J.: First we wondered how people were going to react to the street shooting scenes. But they were hardened against it, thereâs no naivety left in them on that issue, and they perfectly

know how to differentiate between reality and cinema. For the big scenes of extras requiring crowds, it worked perfectly: everybody screamed and ran and then went back taking water quietly as soon as we said âcutâ; the first scene that was shot was a big street sequence with shootings from all sides. I called Elisa LarriĂšre, the executive producer, while I was transiting in an airport en route to the shooting: she told me that everything went smooth. on this type of movie, you have to rely on luck, the first moments are decisive: we can evaluate, from the start, the chances of things working out fine or not.

M.K.: Actors were eager to render reality: they would hit each

other for real to express the violence theyâve endured.

Print

Print